The tiny house movement is gaining momentum in Australia. So what’s the deal with these ever-so-humble abodes?

Blame the Marie Kondo minimalism trend, or the fight against McMansions, but an increasing number of Australians are rethinking what makes a house a home, downsizing their footprint to upgrade their lives. For a small but growing proportion of the population, that means choosing a tiny house.

As our metropolitan and regional centres grow up rather that out, and housing affordability becomes a challenge, some Aussies are of the belief that good things come in small packages. The concept has taken off globally and spawned a number of popular reality TV shows plus a 1.9-million-subscriber-strong YouTube channel called Living Big in a Tiny House. But Down Under the phenomenon is still relatively small.

Dr Heather Shearer, research fellow with the Cities Research Institute at Griffith University and author of Towards a Typology of Tiny Houses, says while Australia’s climate and lifestyle perfectly lend themselves to tiny house living, it is estimated only 200 to 300 people have taken the leap.

“One of the interesting things I found in my research was the wide disparity between people who find them so fascinating and say they would love to live in a tiny house and the very few people who actually do,” she says. Heather explains that while the idea of a tiny house fits with many Australians’ philosophy of living a simple life, the reality of a mini-footprint goes a lot deeper.

What is a tiny house?

Although media might suggest the movement is a minimalist millennial invention, tiny houses have been around since emergency housing was needed after WWII. While there is no formal definition of “tiny house” in Australia, the concept usually refers to dwellings with a footprint of less than 40m2 which can usually be purchased for $50–100,000.

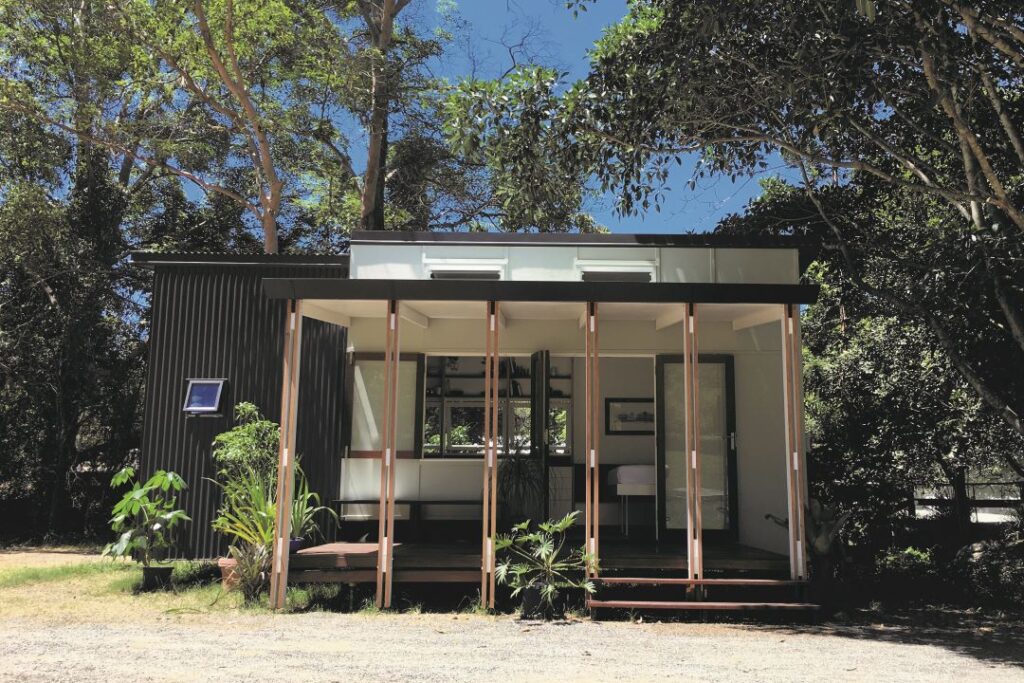

Some are converted shipping containers or refitted buses, while others are purpose-built fixed tiny houses or tiny houses on wheels (THOW), which can be transported like a caravan. But more than just glorified caravans and cabins, today’s tiny houses benefit from modern architectural techniques and technological advances in systems such as solar power, rainwater tanks and composting toilets.

Where can they go?

Buying a tiny house to put on any old suburban block might sound like a cost-effective way onto the property ladder, but it’s not that simple. This is according to Lara Nobel, architect and carpenter with the Tiny House Company, a firm that offers design advice and building services.

“People want a short snappy answer about where they can put a tiny house, but unfortunately you need to consider a number of things,” she says. “Where’s your backyard? What’s your council area? Is your tiny house going to be on wheels? Is it not on wheels? How is connected to the ground, the utilities?”

In conjunction with ESC Consulting, the Tiny House Company produced a planning guide to consolidate a number of frequently asked questions. And while there is no one-size-fits-all answer to where a tiny house can be built or “parked” in Australia, many local councils often break them down into two categories: those with wheels and those without. On wheels, a tiny house is often treated as a caravan and therefore can only really be a “home” for a short period, while those without wheels are often considered a “granny flat” and not to be treated as a primary dwelling.

“What we discovered, and a lot of other people are finding out, is that some councils just don’t know what to do about tiny houses – it really is such a grey area,” Lara says.

Heather agrees there is plenty of room for improvement when it comes tiny houses and how councils treat them. “It’s not that local councils don’t permit them; they just don’t recognise them in their local laws and planning schemes.”

Who can build a tiny house?

Potential tiny house dwellers can purchase plans from a number of specialist companies and head down the DIY route. Or, they can choose to engage a builder. Either way the red tape isn’t the same as a standard house.

“One of my hats as well as being a researcher is as a planner,” Heather explains. “Ideally, from a planning perspective, I’d like to see tiny houses more regulated. Currently, if you build a tiny house on wheels, as long as it adheres to the transport regulations that apply to caravans like electrical and building tickets, it’s okay. But there’s nothing to say they have to be built to any sort of building code because they’re considered vehicles.”

But Andrew Carter, Lara’s partner and another Tiny House Company architect, says for the longevity of the movement and the wellbeing of all those involved, building regulations do need to come into play.

“They’ve been around for such a short period of time that there hasn’t been the necessity for precautions and the building techniques that the industry has tried and tested,” he says. “And as they aren’t specifically tested in the tiny house world, people assume you don’t really need to do it.”

According to Lara, the safest solution for those looking at a tiny house life is to consult an experienced firm. “We come across a lot of people in the DIY category who imagine it’s like building a regular home on a small scale, but if anything making it tiny is far more complicated,” she says.

Why go tiny?

Going tiny gives people all the perks of living in a standard detached home without the mammoth mortgage. And by going down the THOW or off-grid path, owners of tiny houses also claim more freedom.

Lara and Andrew lived in a tiny house for two years before and after the birth of their first child. “It sort of confirmed our suspicions,” Andrew says. “We already knew that we didn’t really need a lot of space. If your storage is customised to suit your needs, you really can scale down and how you use the house is relative to its size.

“It’s not just about reducing the size of a standard house and having it function the same way. It has to be designed differently so that you have overlapping functions for spaces. Everything has multiple uses through the day – it’s essential.”

Andrew says if we look to other cultures we would see most people live in far smaller spaces. “The default is set so high for Australians that we think we need so many things, but if you adjust your lifestyle it’s manageable.”

Lara adds that just because your home is tiny, your lifestyle doesn’t need to be.

“Your house is your retreat,” she says, “but you also use the local parks, cinema, pool, library or coffee shop. You’re out and about more than if you have a big house with a media room and its own pool and double lock up-garage. We felt like we were more surrounded by community.”

Who fits the tiny house mould?

The first rule of tiny house living is that it’s not for everyone, but it can serve a purpose for a number of people in various life stages. According to Heather, the two most common demographics of tiny house dwellers are people in their 20s looking for a first home solution and women over the age of 55 who live alone and either choose to, or are financially required to, downsize their lives.

“It’s a niche solution for a small part of the housing market. Tiny houses serve a specific purpose, and they serve it quite well,” Andrew says. “It’s funny, because we do also spend time convincing people not to buy a tiny house after getting to know them and what they’re really chasing. I think some people get swept up in this idea of them without fully considering what it involves.”

If you’re considering going tiny, here are a few helpful resources:

Australian Tiny House Association

Tiny Houses Australia Facebook Page

The Tiny House Company

The Tiny House Resource Guide