Cats and foxes – both introduced species in Australia – devastate native wildlife, and put our most vulnerable animals at risk of extinction. Several experts believe that the time to act is now with the help of a device called a Felixer.

A feral cat captured on camera in arid South Australia, Credit Hugh McGregor, Arid Recovery

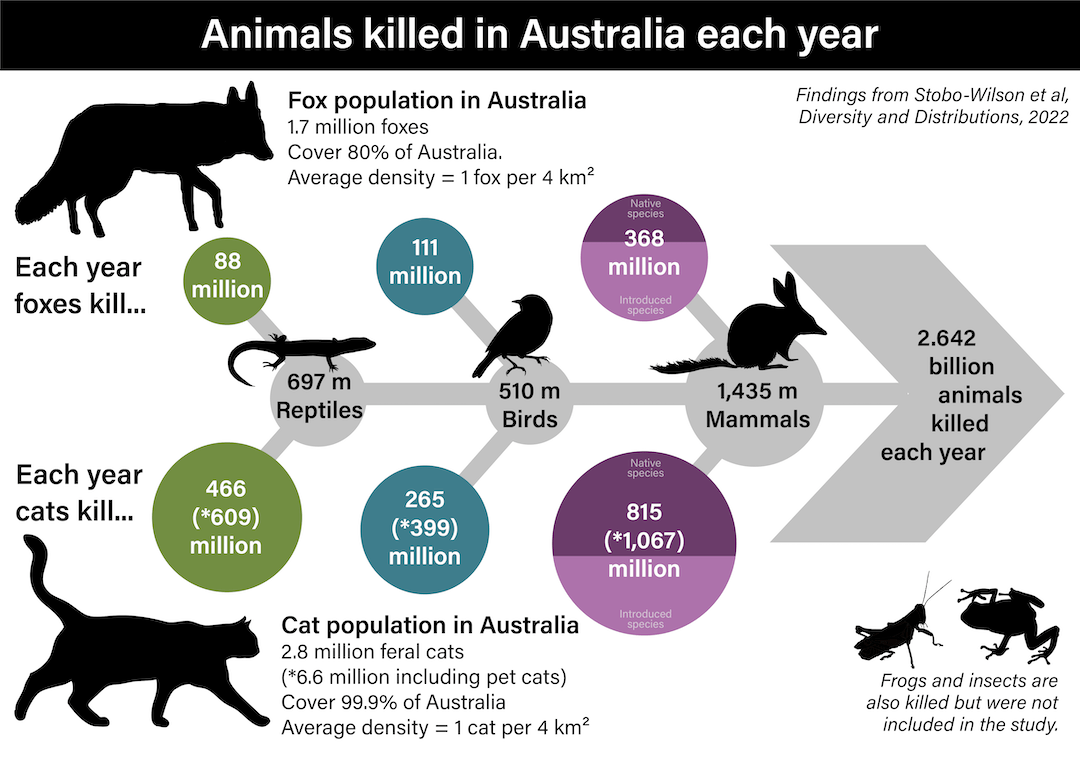

When you remove the association with cute and cuddly cartoons in timeless Disney classics, our perception of cats and foxes changes dramatically. In fact, scientists from 13 institutions across Australia have found that 697 million reptiles, 510 million birds and 1.4 billion mammals are killed by feral cats and foxes each year.

Adjunct Researcher Dr Alyson Stobo-Wilson from Charles Darwin University gives dire warnings that without better control, the predators will continue to wreak havoc on many native species that are already struggling.

“This research gave us a clearer picture of the impact of both species nationally and in different and remote environments,” she says. “Estimating feral animal density was an important first step to understanding the impact of foxes and cats in different environments. We found that fox densities and impacts are highest in temperate southern mainland Australia. In temperate forests they collectively kill up to 1,000 animals per square kilometre per year.”

Alyson Stobo-Wilson with a northern savanna glider.

Co-author Professor Trish Fleming – Director of the Centre for Terrestrial Ecosystem Science and Sustainability at Murdoch’s Harry Butler Institute – believes the native animal death toll is all we need to pursue more effective fox and cat control.

Cats and foxes are fast, agile, cunning by nature, and own razor-sharp fangs that are no match for native Australian species. They also both have a generalist diet, meaning they can adapt to whatever prey is available – leaving few species untouched. Their ability to hunt in various environments makes them the ultimate predators.

“Most of Australia has no effective management practices in place and so the impacts on biodiversity are likely to be severe, widespread and ongoing,” says Trish.

Turning back the clock

Foxes were introduced to Australia in 1855 for recreational hunting. During the next 100 years, foxes rapidly established themselves across the majority of the continent. Similarly, cats arrived with early European settlers in the 1800s – despite theories that they arrived as early as 1650 aboard Malaysian fishing boats – according to research from the BMC Evolutionary Biology journal.

Once widespread across Australia, by 1863 the burrowing bettong was completely wiped out of Victoria, and in a few short years they no longer occupied the mainland at all. The Australian Wildlife Conservancy acknowledges that this was largely due to predation by feral cats and foxes. Establishing predator-free areas on islands and exclusion fencing, such as the conservation fence in Scotia Wildlife Sanctuary, New South Wales, has seen great results in protecting native species.

Diagram of the number of animals eaten by cats and foxes per year in Australia.

The Return to 1616 program is in action until the year 2030, with the aim of returning Dirk Hartog Island off Monkey Kia in Western Australia to pre-settlement condition. The program aims to re-introduce 12 mammal species and one bird species, and eradicate feral animals from the island.

Former Greens leader Richard Di Natale said Australia has “one of the highest loss of species anywhere in the world,” which ABC Fact Check investigated and found to be true.

Unfortunately, more than 10 per cent of the animals known to inhabit mainland Australia in 1788 are now extinct, predominantly because of feral animal predation, according to The Guardian’s environment editor Adam Morton.

Trial and error with Felixer, and now success

Sold under the brand name 1080, sodium fluoroacetate is a poison used predominantly in Australia and New Zealand to eradicate pest species. The active ingredient fluoroacetate naturally occurs in some plant species in Australia, meaning native Australian animals are a lot more tolerant to it, according to Dr John Read, Founder and CEO of the Thylation group of companies – cofounder of the Arid Recovery, Wild Deserts and Mallee Refuge conservation projects and chair of the Warru (rock wallaby) Recovery Team.

1080 baits are often deployed by aircraft in vast quantities or by hand in targeted areas. However, the Felixer has also been developed as an additional targeted tool for cat and fox control through research, grants and trials.

“The idea was to develop an automated pest control system that didn’t have to be checked all the time, a system that is more targeted and hence better for animal welfare,” says John.

“LiDAR laser beams determine the size and speed of animals walking past the Felixer. The sensors trigger a spring that squirts the sealed dose of 1080 poison gel at 50 metres a second onto the cat’s (or fox’s), fur which they then run off to lick and subsequently die. The Felixer will reset itself (it’s capable of holding up to 20 gel cartridges), ready for the next cat to walk by,” he explains.

Felixer at Kalka, Credit John Read

“The Felixer is designed so that it is very unlikely to fire at adult dingoes – or any other native species for that matter – and this is proven by stable dingo populations in areas where Felixers are set. It’s a system that puts far less poison into the environment,” says John.

Currently Felixers can only be leased to people with a 1080 permit, and the researchers are still operating under a research permit, so any leaseholders also need authorisation by a government agency.

“Mining companies, conservation workers, national parks and Aboriginal communities are using it at the moment,” says John. “It’s still early days so Felixers aren’t generally available for farmers or private residents yet.”

The Felixer V3.1 by Thylation on screen.

Each time an animal walks past a Felixer the machine takes a photo, so researchers can monitor animal movements in the area.

“We can make them smarter and smarter and improve the way they work. Even now, if an animal that’s too big travels past, like a kangaroo or a cow, the whole thing shuts down. Even if the animal stretched out or did something that looked a bit different it would still shut down,” says John.

“In one instance, during low tide a fox made its way across to Bird Island just off Adelaide, where there are rare fairy terns nesting. Rangers took a Felixer over to the island and they found the dead fox soon after.”

Combining recovery efforts

Arid Recovery is an independent not-for-profit organisation operating in South Australia, pioneering conservation science to help threatened Australian species. It trialled 20 Felixers in a 6,300 ha section of reserve in the arid north of the state, where feral cats, bettongs and bilbies all live. According to Arid Recovery, the Felixers had great success in decreasing the cat population as well as not firing gel cartridges at a single non-target animal. Since the experiment, and thanks to donations, Arid Recovery purchased its first Felixer in 2020, and has been using it for feral cat control.

If you would like to help Thylation develop the Felixer, head to thylation.com to find out more. “If people want to enquire about leasing a new v3.2 Felixer, which will come equipped with artificial intelligence, donate, or even provide suggestions or anything like that, it would be well received,” says John.

Superb fairy-wren in a burnt landscape on Kangaroo Island, Credit Nicolas Rakotopare