Hunted to the brink of extinction, the saltwater crocodile has made a stellar comeback, creating a bunch of lucrative agricultural side businesses in the process.

Saltwater crocs and the beginning of Australia’s crocodile industry

“Shoot the lot of them.”

That was the general consensus towards the estuarine or saltwater crocodile in Australia until a few generations ago. And that we did, using Aboriginal labour and guidance to hunt them for their skins – to the brink of extinction. By the early 1970s, crocodile numbers had dwindled to less than 3000; so, the species was added to the endangered list and hunting the was banned.

Today, there are an estimated 150,000 saltwater crocodiles in the Top End. This makes the Northern Territory the beneficiary of the most effective predator-conservation program ever conceived. Its success is credited to the concurrent launch of incentive-based income streams. These include crocodile farming for leather and meat, and a crocodile tourism industry sector underpinned by our love-hate relationship with the world’s most efficient predator.

We speak with three business owners in the crocodile industry who have helped save the saltwater crocodile from humanity’s reptilian nature.

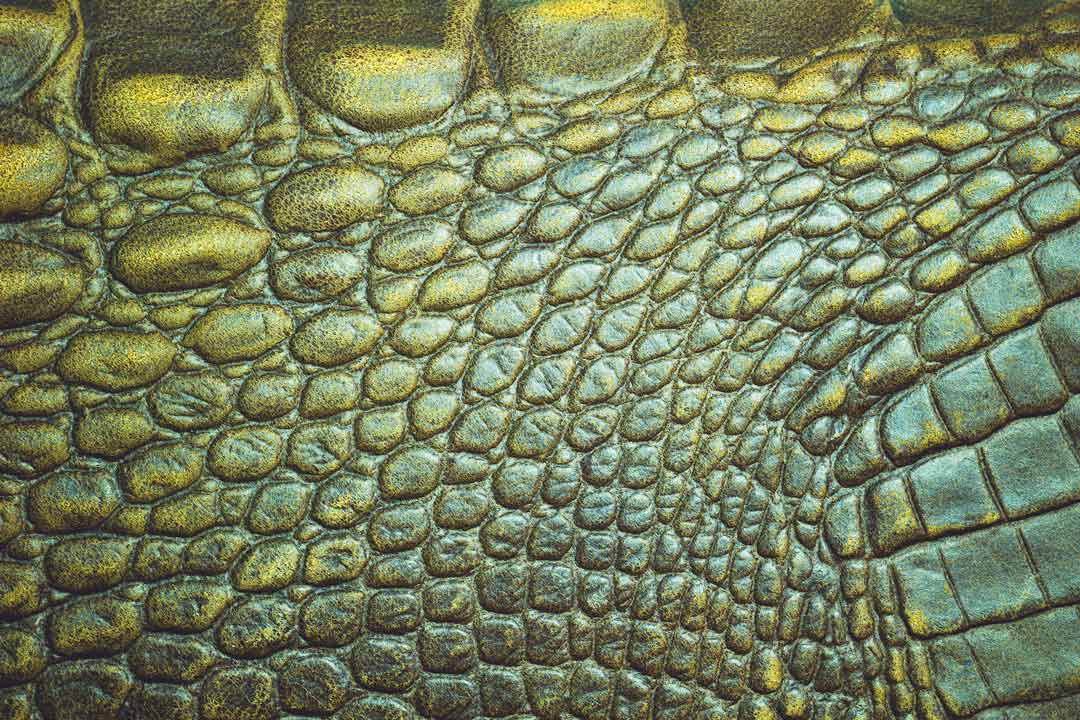

Farming for fashion: the crocodile skin industry

When Aaron Rodwell was a kid, he emptied the family swimming pool and turned it into a reptile enclosure. When he grew up, he got a special permit to remove problem crocodiles from the wild that pose a threat to tourists and cattle stations. Ten years ago, the Darwinite’s relationship with the predators led him to create Croc Stock and Barra; a crocodile fashion and apparel leather in a class of its own.

“Never kill an animal unless you’re going to use or eat all its parts. That’s how I roll,” Rodwell says. “I use parts that normally get burned at the crocodile farms into products. I make backscratchers from the claws, jewellery from the teeth, and I make taxidermy skulls for collectors and universities. The crocs I kill in the wild; their skin is too tough and old to make products, so I sell them as trophy skins.”

Farmed crocodile skin is mostly used for handbags, and Australian saltwater crocodile skins are considered the best in the world. The big European fashion houses can’t get enough of it. So about five years ago two of the biggest – Louis Vuitton and Hermès – bought 12 out of 14 crocodile farms in Australia. Their least-expensive crocodile handbags sell for around $50,000. Others go for more than twice that much.

But Rodwell’s handbags, made from crocodile backstraps and crowns, sell for much less: $500 to $1500.

“Those big companies, they’ve monopolised the market and made it hard for Australian producers to find skins,” he says. “But I have a special relationship with the farmers because I turn their trash into cash. What farmer in the world wouldn’t like that?”

The croc industry meets animal agriculture

Low in fat and cholesterol but rich in protein, crocodile meat is not only good for you; it makes you look good too, thanks to its high colloid content, which delays the onset of wrinkles. But how does it taste?

“It’s not quite fishy, not quite meaty. It has a neutral taste, like a cross between seafood and chicken,” says Marnie Flanagan of Naturally Wild. Marnie is a supplier of Australian-farmed buffalo, boar, venison and crocodile meat. “I always compare it to calamari – light white meat that goes very well with lemon butter and salt.

“When I started in 2010, I did shelf tests with the supermarkets to see what cuts of meat sold,” she recalls. “One of the barriers we found is that people didn’t know how to cook croc. Like all game meat, it’s easy to overcook, turning it tough and leathery, and those consumers never come back.”

“So, to make sure they wouldn’t be disappointed, we tried ready-to-heat meals – crocodile green and red curries. But they weren’t big sellers, so we went back to the square one. We then figured out crocodile tail steak was a winner because it’s the most tender part of the animal. We also do sausages that are 90 per cent crocodile meat with rice flour added.”

The crocodile meat industry in Australia remains small because of limited supply and relatively high price. A 250-gram crocodile steak sells for about $13 at Coles – more than $50 a kilo.

“The people who buy it tend to be health freaks looking for low-fat meat that’s unsullied by antibiotics,” Flanagan says. “It’s also popular among food adventurers and people who’ve travelled overseas and tried game meat on safaris in Africa and aren’t geared on the repetitive Australian diet of beef, lamb and chicken.”

The crocodile industry turns to tourism

Between 1984 and 1988, visitor numbers at Kakadu jumped from 75,000 to 200,000. Peter Hook of Kakadu Tourism credits the spike to our sharp-toothed friends. Mostly, thanks to Paul Hogan’s Crocodile Dundee and the opening of the Crocodile Hotel in Jabiru.”

Visitor numbers in Kakadu have taken a hammering over the years but have now surpassed 1988 levels. The region received 200,577 visitors in 2018. Nearly every single one of them will buy a ticket for a jumping crocodile show on the Adelaide River.

“It’s like when you go to Paris, you see the Eiffel Tower. When you come to the Northern Territory, you go to see the crocs. It’s on everyone’s must-do list,” says Maxine Bowman of Adelaide River Cruises. She works for one of just three tour boat operators on the waterway.

“The other two companies are much bigger than us and have bigger boats. Ours is just a little family business,” she says. “We only have two boats that can take a maximum of 45 people twice a day, but that’s part of the appeal. Our boat drivers are two brothers who’ve been doing the same job for 20 years. We offer tourists a more personalised experience.”

Animal welfare groups have voiced concerns about operators that coax crocodiles to jump out of the water. They say it changes the predator’s behaviour and encourages them to attack human beings.

But Bowman says that’s bull: “Crocs jump naturally in the wild. I have personally seen egrets perched on low-lying branches or walking along the bank of a river when all of a sudden you hear this massive whoosh as a crocodile exploded from the water for lunch. It’s the greatest show on earth.”