The elusive rat kangaroo that was previously thought to be extinct, could still be roaming the outback.

The native Australian rat kangaroo, previously thought to be extinct, may still be running in the remote Sturt Stony Desert, and Flinders University researchers have discovered new details about its feeding habits that may help locate it.

Marsupial evolution and ecology experts have compared the bite strengths of different small animal skulls to understand the kinds of food the desert rat kangaroo (Caloprymnus campestris) ate, thus narrowing down possible habitats for the elusive little creature.

“Rat kangaroos, like bettongs and potoroos, are an ideal group of animals for testing skull biomechanics, because they each have different shaped skulls and specialise on very different food groups,” says Dr Rex Mitchell, lead author of a new article published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

“We were surprised to find the heftier skull of the desert rat kangaroo isn’t necessarily adapted for biting into harder foods. When we included the animal’s smaller size into the analysis, the robust features of the desert rat kangaroo’s skull were only found to be effective enough to handle eating a softer range of foods,” he says.

The latest research could help efforts to rediscover the desert rat kangaroo (known as ngudlukanta to the traditional custodians of the region – the Wangkangurru Yarluyandi people) after unsubstantiated reports of a distinctively small, short-faced, hopping animal in the vicinity of its home range in the Lake Eyre Basin in remote far north-east South Australia and Queensland.

WHAT LED TO THE RAT KANGAROO’S EXTINCTION?

Predation by foxes and cats, competition with rabbits, overstocking of cattle and sheep, and poor fire management pushed the desert rat kangaroo to possible extinction. The small desert-dwelling potoroid marsupial is now known from only a handful of museum specimens that were gathered from inaccessible areas of South Australia.

Senior author of a new study, Flinders University Associate Professor Vera Weisbecker, says: “It is plausible that a small, nocturnal species could be evading detection in the vast inland desert. In fact, this species was previously a resurrected ‘Lazarus’ species after its rediscovery in the 1930s.

“So regardless of whether or not the species persists in the Sturt Stony Desert or elsewhere, the story of the desert rat kangaroo serves as an ongoing reminder that extinction declarations might not always be the end of the story,” she says.

This new-found evidence of the creature’s feeding habits could help to shift search efforts into specific regions where the plants it eats, grow.

The desert rat kangaroo was known to eat mostly leaves of plants, but its short round face led researchers to suggest that, if needed, it could eat harder foods as well, such as seeds and twigs.

“Fine tuning the search through understanding the animals’ diet better might just resurrect the little desert survivor once more,” adds Dr Mitchell.

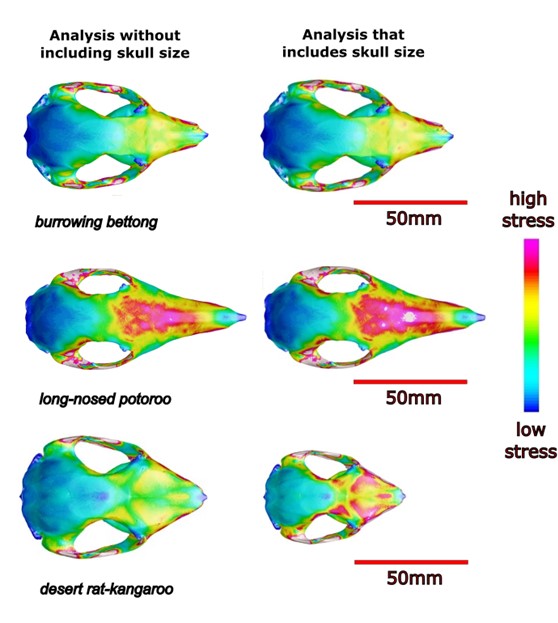

Models comparing the stress of each skull during biting with the front teeth. The stress in the desert rat kangaroo is more similar to the burrowing bettong when not including its small size in the models. But its stress levels are more like the long-nosed potoroo when including its small size. Image provided by authors.

USING NEW TECH IN THE STUDY OF SKULLS

Using computer models of historic skeleton specimens, the new study uses a method called Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to test the skull’s ability to handle the forces that happen during a bite.

The skull of the desert rat kangaroo was compared with the skulls of short-faced specialists of harder foods like the burrowing bettong, or boodie, and the specialists of softer fungi like the long-nosed potoroo.

The researchers say these kinds of studies give valuable insights into the relationship between skull shape and biting ability, with applications towards animal behaviour, conservation, ecology, evolution and palaeontology.

The paper, ‘Testing hypotheses of skull function with comparative finite element analysis: three methods reveal contrasting results’ (2025) by D Rex Mitchell, Stephen Wroe (University of New England), Meg Martin (WA Museum) and Vera Weisbecker (also affiliated with ARC CABAH, Wollongong) has been published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

If you enjoyed this story on the rat kangaroo, check out one of our other stories here.

Acknowledgements

The lead authors were funded by Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CE170100015) and an ARC Future Fellowship (FT180100634) to VW. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Microscopy Australia and the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) under the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy, at the South Australian Regional Facility, Flinders Microscopy and Microanalysis, Flinders University. Also David Stemmer of the SA Museum. This research was conducted on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people.