Scientists have found that the world is 1.7 degrees warmer, according to information gathered from the Puerto Rican sea sponge.

Researchers from The University of Western Australia collaborated with experts from Indiana State university and the University of Puerto Rico to analyse sea sponges in the Caribbean. They found that ocean temperatures may be 0.5 degrees warmer than previously estimated, sparking major conversations around the impacts of climate change.

A difficult task

In 2015, the world’s nations signed the Paris Agreement in an effort to limit global warming from reaching more than 1.5 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels. However, monitoring changes in the earth’s temperature has proven difficult due to the lack of information establishing temperatures before the Industrial Revolution.

This was the concern raised by scientists in a new paper published in the Nature Climate Change journal, when they set out to discover a way of measuring global temperature levels in the 1700s.

The experts faced several challenges when collecting this data. Firstly, a series of large volcanic eruptions in the 1800s caused large-scale cooling because of ash in the atmosphere, a phenomenon not seen in recent history. Additionally, methods of recording global sea temperatures only began in the 1850s, meaning the pre-industrial period is largely unaccounted for.

Collecting sea sponge samples © Clark Sherman

Super sponges

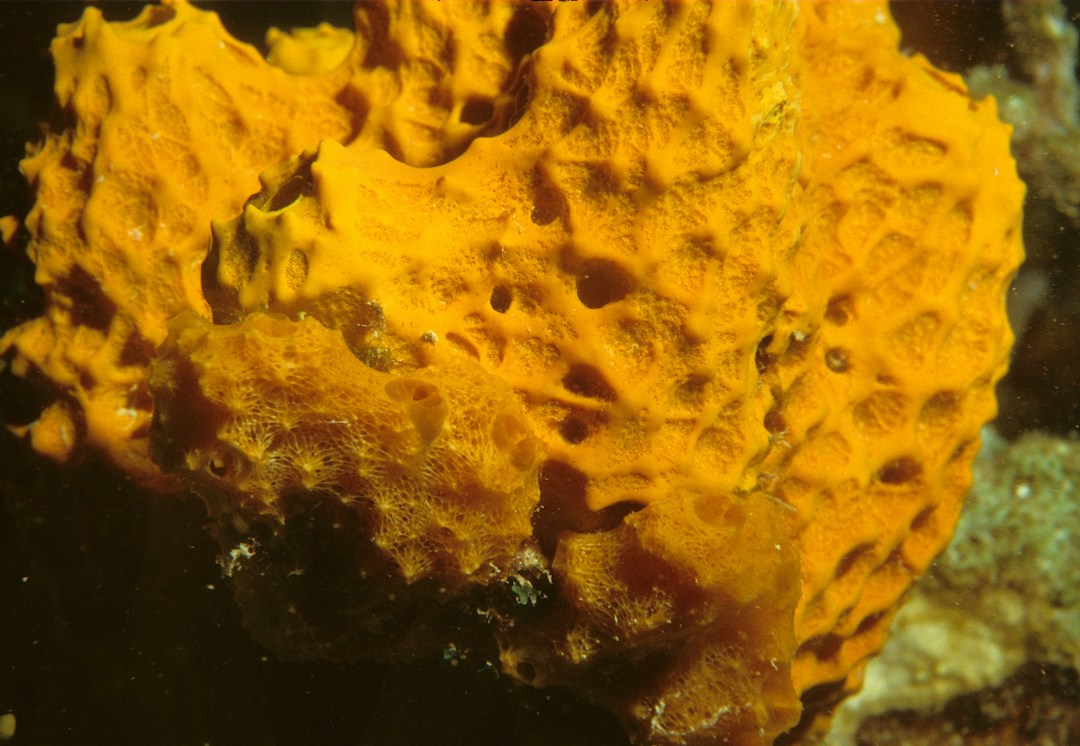

In order to ascertain the temperature in this period, scientists turned to the Puerto Rican sea sponge, an ancient species of calcifying sponge resembling a mound of foam and usually attached to a rock. Over time, these sea sponges will grow additional layers, providing scientists with a continual record of temperature throughout their lifetime

Experts analysed the calcium carbonate skeletons of sea sponges, which contained 300 years of ocean mixed-layer temperature records, finding that temperatures were higher than previously anticipated.

Lead author Professor Malcom McCulloch from the University of Western Australia’s Oceans Graduate School and Oceans Institute, explains that this information reveals global warming has been underestimated by around 0.5 degrees.

“So rather than the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimate of average global temperatures having increased by 1.2 degrees by 2020, temperatures were in fact already 1.7 degrees above pre-industrial levels,” he says.

A Puerto Rican sea sponge © NOAA

The larger implications

This revelation has sparked conversation in scientific circles, with many believing this calls for a recalibration of international climate efforts while others argue that findings from one location don’t dictate the global reality.

For Professor McCulloch, this research presents more challenges to emissions targets, and emphasises the importance of prioritising clean energy.

“If current rates of emissions continue, average global temperature will certainly pass 2 degrees by the late 2020s and be more than 2.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels by 2050,” he explains.

“The now much faster rates of land-based warming also identified in the study are of additional concern, with average land temperatures expected to be about 4 degrees above pre-industrial levels by 2050.

“Keeping global warming to no more than 2 degrees is now the major challenge, making it even more urgent to halve emissions by early 2030, and certainly no later than 2040.”

To learn about the benefits of water recycling to cool the earth, click here.