What post-pandemic crisis? The future is bright for Australia’s mining sector.

The outlook for mining in Australia has never looked brighter. That’s the gospel according to every analyst in the sector, which is experiencing conditions similar to the boom of 2010, and then some. Growth is being driven by unending demand for coal and iron ore plus a rejuvenation in strategic metals such as copper, nickel, zinc and lithium.

“We’re going through a period that’s been as good as we’ve seen probably in 20 or 30 years,” says Warren Pearce, CEO of the Association of Mining and Exploration Companies.

But it’s not going to be business-as-usual in the new boom. Rising environmental, social and governance concerns mean mining companies are going to have to do and be seen to be doing a lot more to earn and maintain their social licence and attract the best people to fill jobs.

We take a closer look at the multibillion-dollar opportunities and make-or-break challenges in what is gearing up to be the most exciting and transformative era in the history of mining.

“There is a growing demand for the minerals integral to renewable energy, electric vehicles and energy storage systems,” says Paul Mitchell of EY.

Bread and butter of Australia’s mining sector

Last year mining companies benefited from higher commodity prices and a weaker Australian dollar, which saw export earnings hit a record $310 billion. This year the country’s mining and energy exports are estimated to smash that record again, reaching $425 billion, according to the Australian Government’s March 2022 Resources and Energy Quarterly report.

Despite the headlines, coal continues to account for more than a quarter of these earnings as it remains a key source of global energy. “China, India and Russia make up 50 per cent of global electricity consumption – 70 per cent is from burning coal,” Jessica Amir, Australian market strategist at Danish investment bank Saxo, told the Investing News Network. “Global electricity generated from coal surged 9 per cent to a new record high in 2021.”

Australian iron ore exports are also looking strong, with production set to increase by 2 per cent this year on the back of new projects that began operations in 2021. Australia’s two largest miners, BHP and Rio Tinto, expect iron ore production to increase by nearly 17 per cent compared to 2021.

“There is a significant opportunity for Australian miners to build or expand processing and refining capacity,”

But the absolute dominance of these commodities will soon start to wane. “Historically, the Australian mining sector has been focused on iron ore and coal, whereas we are seeing a rejuvenation in the base metals such as copper, nickel and zinc, along with a rapidly expanding lithium sector,” says David Franklyn, executive director of Argonaut, a corporate advisory firm in Perth.

Copper prices hit a record high in 2021 in Australia’s mining sector.

New boys in town

Demand for base metals is being driven by the electrification revolution that will power transport for decades to come. And it’s sending prices of base metals used to make rechargeable lithium-ion batteries to the moon. Copper prices hit a record high in 2021 while the spot price for lithium jumped more than 600 per cent in the first half of this year. Citigroup projects more “extreme” price hikes are likely for lithium in the second half of 2022 – which spells good news for Australia, the world’s largest producer.

“There is a growing demand for the minerals integral to renewable energy, electric vehicles and energy storage systems,” says Paul Mitchell of EY. This means more demand for battery metals such as lithium, nickel and cobalt as well as rare earths.

Professor Matthew Hill, deputy head of chemical and biological engineering at Monash University, adds: “We are going into a commodity super-cycle as we electrify everything.”

Demand for hydrogen, a gas made with renewable energy that will be the key to decarbonising hard-to-electrify sectors like trucking and steelmaking, is also on a steep upwards trajectory. Australia, which has vast areas where either sunshine or wind is in near-constant supply, is emerging as the regional hub for green hydrogen production. In fact, the Australian government estimates hydrogen exports and domestic use could generate more than $50 billion within 30 years.

Paul agrees: “Australia has the opportunity to be a green energy powerhouse if it has the political will and foresight, endowed with vast reserves of lithium, nickel, copper, rare earths, uranium and plenty of wind and sun, to drive renewable energy production.”

Remote mining towns in Western Australia and Queensland are also looking toward hydrogen and base metals as a way to mitigate the boom-bust cycle that has dogged Australian mining communities since the very first gold rush of 1851. “Relying on six commodity prices certainly helps level out the field,” Tony Simpson, CEO of Regional Development Australia’s Pilbara office, told the ABC. “The more we can diversify, we’re not relying on one commodity price or two.”

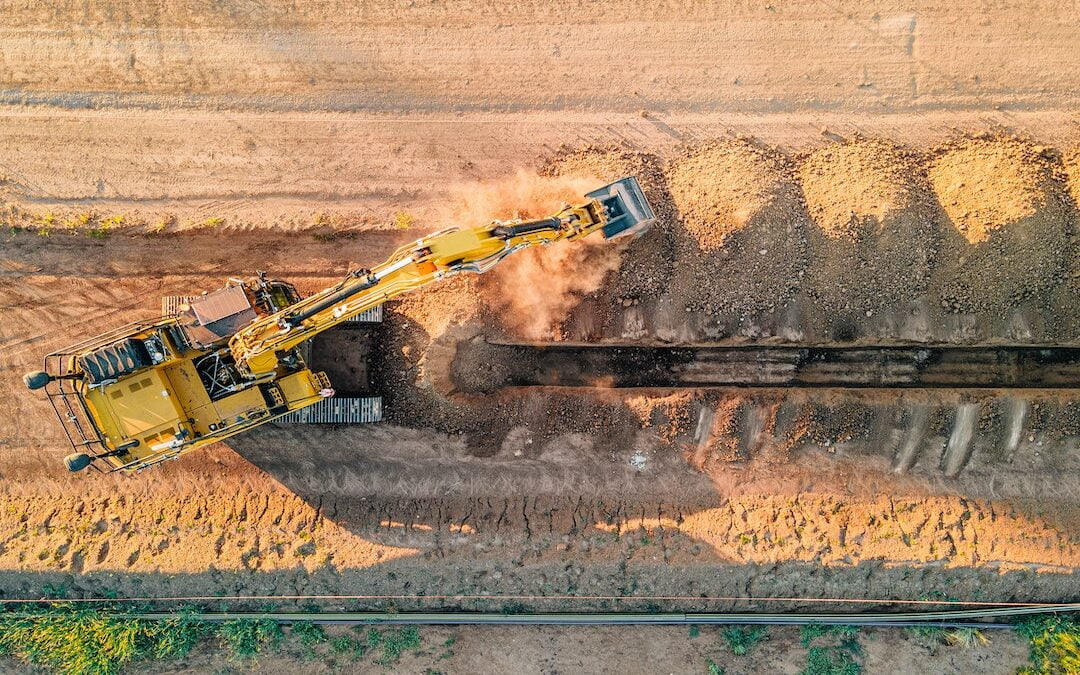

Do no harm: a key focus in 2022 and beyond will be how to extract minerals from the ground without impacting local communities and ecosystems.

People and the planet

To make good on these opportunities, mining companies are going to have to solve staff shortages that have put a dent in production in Australia during the pandemic. Rio Tinto’s iron production declined 3.3 per cent last year compared to 2020, due to labour shortages and commissioning delays, while a shortage of train drivers and weather-related disruptions saw BHP’s iron ore supply increase by only 0.1 per cent in the same period.

Accenture head of natural resources David Burns believes a more individualistic approach to human resources, which looks at every dimension of every worker, will help solve the deficit. “Acknowledging and adapting to this reality can help mining companies operate with greater understanding and empathy, ultimately transforming their workplace – and the workforce,” he told Australian Resources & Investment, a mining journal. New technologies, such as drones to carry out pit surveillance and autonomous trucks and trains, can further devise new ways to gain efficiencies, he added.

But the biggest challenge to unlocking more value in the sector will be meeting – and exceeding – environmental, social, and governance (ESG) requirements in a low-carbon, low-waste, purpose-driven future.

“ESG is no longer optional or a point of differentiation. It is the minimum operating standard,” says Paul Bendall, global mining leader at PwC. “Stakeholders are increasing the pressure, and strong social licences, responsible divestitures and tax transparency will be important for success.”

Professor Neville Plint, director of the Sustainable Minerals Institute at the University of Queensland, reckons a key focus in 2022 and beyond will be how to extract minerals from the ground without doing any harm whatsoever to local communities and ecosystems. “[Mining companies] must show how they are working positively with local communities, how they are mining responsibly and sustainably, and how they are contributing to a low-carbon economy,” he says, adding that new ESG requirements must be carried by every single person working in the industry.

For more on mining in Australia, check out future mining trends for 2023.