Recordings of underground acoustics can help experts to determine the health of our soil, according to a new study.

The report, led by ecologists from Flinders University, found that soundscapes barely audible to human ears can be used to identify the diversity of animal life living in the soil. This has major implications for monitoring and protecting soil health in the future.

Soil is home to an abundance of life.

Importance of soil health

Currently, 75 percent of the world’s soil is degraded, threatening the multitude of living creatures that make their habitats underground. In fact, almost 60 percent of the Earth’s species live in this secret ecosystem. According to the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, soil microorganisms and microfauna transform organic and inorganic materials into food for other plants and animals, acting as a vital part of their ecosystems and the food chain.

Dr Jake Robinson, from the Frontiers of Restoration Ecology Lab at Flinders University, believes that this reveals why it is vital for experts to continue monitoring this environment.

“Restoring and monitoring soil biodiversity has never been more important,” he says.

“Although still in its early stages, ‘eco-acoustics’ is emerging as a promising tool to detect and monitor soil biodiversity and has now been used in Australian bushland and other ecosystems in the UK.”

Process of capturing soil acoustics explained.

Digging deep

The study, which took place in the Mount Bold region of South Australia, compared results from acoustic monitoring of vegetation plots from 15 years ago which were revegetated after a period of degradation.

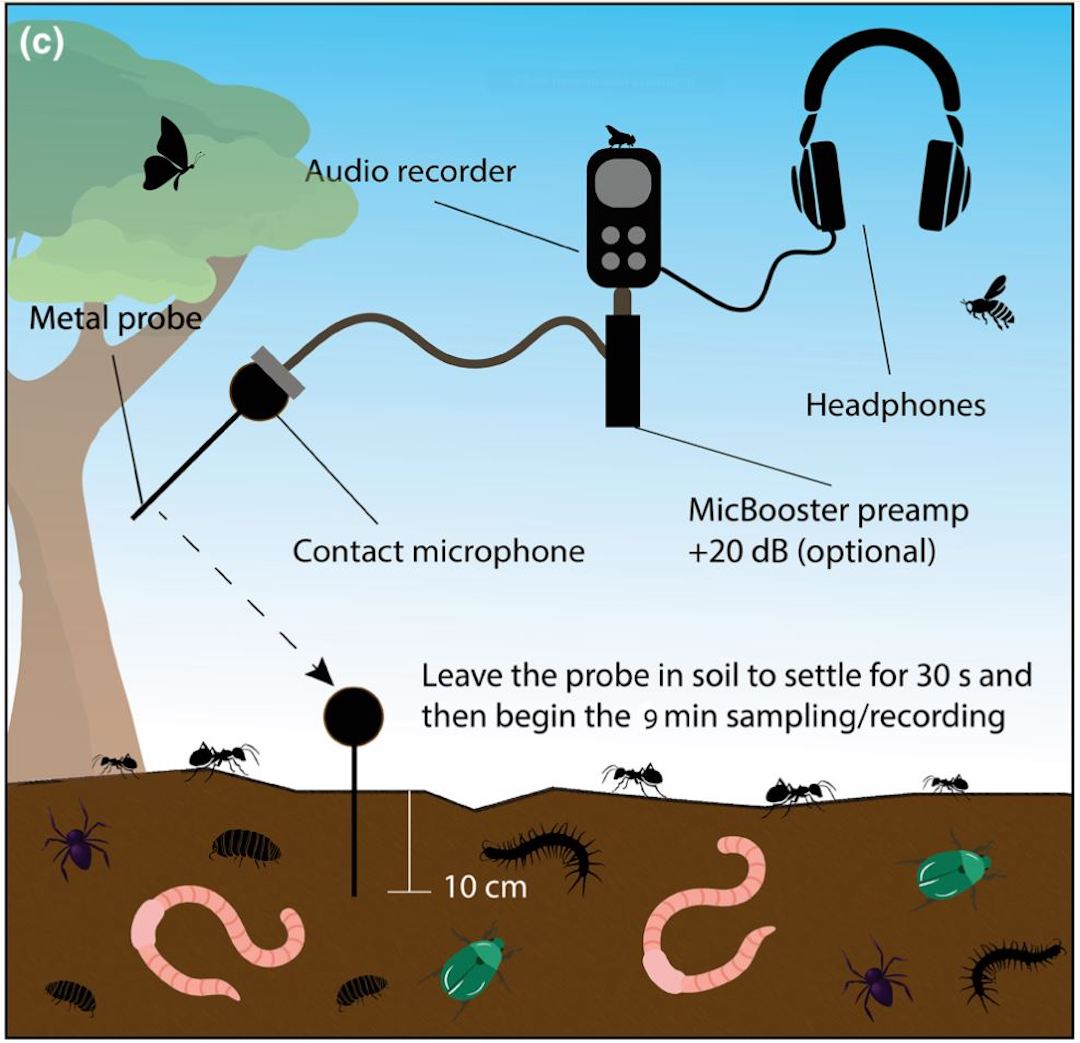

Using a variety of tools and indices for passive acoustic monitoring, the team was able to measure soil health over five days in the chosen region, tracking several important factors. In order to record invertebrates in the soil, below-ground sampling devices and sound attenuation chambers were utilised.

“It’s clear acoustic complexity and diversity of our samples are associated with soil invertebrate abundance – from earthworms, beetles to ants and spiders – and it seems to be a clear reflection of soil health,” says Dr Robinson.

“All living organisms produce sounds, and our preliminary results suggest different soil organisms make different sound profiles depending on their activity, shape, appendages and size.

“This technology holds promise in addressing the global need for more effective soil biodiversity monitoring methods to protect our planet’s most diverse ecosystems.”

Dr Jake Robinson in the field.

Acoustic answers

The study has been published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, and researchers hope it will encourage further focus on soil monitoring and underground acoustics.

“The acoustic complexity and diversity are significantly higher in revegetated and remnant plots than in cleared plots, both in-situ and in sound attenuation chambers,” says Dr Robinson

“Acoustic complexity and diversity are significantly associated with soil invertebrate abundance and richness.”

By establishing a measure of soil health and numbers of invertebrates, experts may be able to effectively protect this overlooked ecosystem in the future.

Featured image: The Flinders University team conducting a study on underground acoustics.

To read about the researchers using AI to count flamingo populations in Botswana, click here.