America’s new Vice-President represents how high women can go, but also the obstacles they must overcome to get there, says Macquarie Business School Professor of Gender, Work and Organisation Alison Pullen.

As Kamala Harris is sworn in as the first female and the first Black Vice-President of the world’s most powerful nation, she sends a message to women everywhere that anything is possible.

“Every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities,” Harris said in her acceptance speech in November following her and Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election.

But those little girls, in Australia as much as America, must be incredibly exceptional and do extraordinary things to reach the top, says Alison Pullen, Professor of Gender, Work and Organisation at Macquarie Business School.

“There are institutional and societal barriers that prevent women from reaching these lofty heights,” says Pullen, who is also Co-Editor-in-Chief of the journal Gender, Work and Organization.

“And women are always held to higher standards than their male counterparts; they have to be so much better, and so exceptional on so many levels.”

For young women who are inspired by Kamala Harris – and indeed, Australia’s first female prime minister Julia Gillard before her – they should know that to reach the top, they will face organisational structures that are yet to genuinely embrace diversity. It will take hard work, determination, focus, planning and building relationships, in addition to doing their actual job, says Pullen.

Here are some research-based tips for how these leaders of the future can navigate their way up the ladder.

Know the barriers and stay focused

Pullen believes Harris’s background is key to understanding her rise.

“Kamala is speaking very directly about being a role model in terms of empowering and inspiring other women, but she never, ever talks about herself, or other women, without talking about her mother, and I think this is very important,” Pullen says.

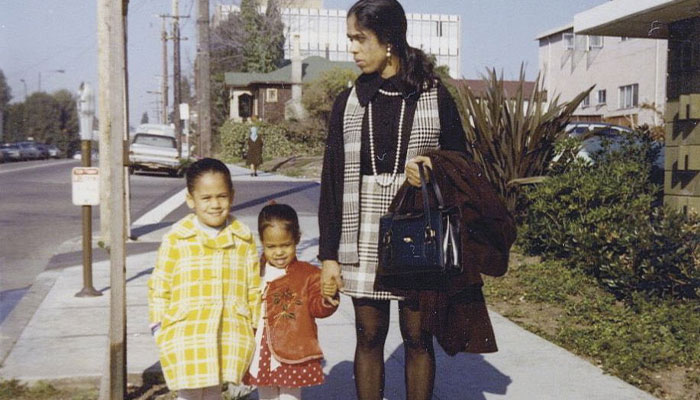

Kamala’s Indian mother Shyamala Gopalan, the daughter of a high-caste civil servant, arrived in the US aged 19 to study at the University of California Berkeley.

“This was exceptional …. people talk about her being one of the few Indian women in the entire country when she arrived in 1958, and she was a minority woman at Berkeley, but it didn’t matter: she was focused, she knew where she was going and she had a path to follow.”

Shyamala’s marriage to Kamala’s father Donald Harris, a Jamaican-American academic and economist – Shyamala herself became a renowned breast cancer researcher – was very radical at the time.

“Not only did she not have an arranged marriage, but the family hadn’t met or approved of him,” Pullen says.

“As academics, they clearly had aspirations for their two daughters, and Kamala’s mother raised them to be fully aware of the discrimination they would face and how they needed to work through it and move on past it.”

A young woman in a workplace in Australia today, particularly an immigrant or ethnically diverse woman, says Pullen, will know the discrimination they are facing “because you can feel it, see it, hear it … to be aware of that and to focus on your career trajectory and plans is an important starting point”.

“Women,” she says, “need to focus on what they want, and not let the barriers and the discriminatory practices put them in a position where they don’t move through them or don’t, in some cases, fight against them.”

Male networks that exclude women from particular positions can make it very difficult for determined women to break through the glass ceiling, a reason they don’t make it to the top in the same numbers as men.

“It entails a battle in male-dominated environments, and those that do break through are often elite women who have focused on the job at hand and, regardless of how they are identified by others, reached senior positions.”

Be resilient

The ability to bounce back from knock backs and rejection marks the exceptional women who succeed in their upward climb, Pullen says.

“When they face the discrimination, it is the women who go, ‘ok, that hurt, it is going to take me a few weeks to get over this’, but who continue and come back even more determined, that succeed.

“Any woman that reaches significant positions in Australia would have those qualities because those rejections are a normal part of what you go through.”

Find mentors, and know when to move on

From the outset of a career, building relationships is crucial, particularly relationships with mentors who can work with you to develop your sense of focus about where you want to go, Pullen says.

“Women often talk about the importance of mentoring within organisations in order to develop their career – and sometimes that can mean leaving,” she says.

“When I think about people I have researched, exceptional women know that when you face particular systemic organisational blockages – that is, cultural or structural barriers that you cannot navigate or work through – you have to go elsewhere.

“So you will see very successful women often moving through organisations … so it’s a case of not resting, and not actually putting up with the discrimination you experience.”

That does not mean discrimination should not be called out, and the same applies to bad leadership that perpetuates discrimination, and worse.

When an ambitious young woman comes up against a toxic line manager, Pullen says, she or trusted colleagues if they are able should speak out against it, and expect the organisation to address it.

“Usually, however, organisations protect people until it gets really bad; there is an acceptance or a tolerance of bad relationships in organisations,” she says.

“We need to seriously think what organisations need to do to avoid the wrong people occupying important roles in terms of the development of people.”

Confronting the structures

Professor Pullen is a chief investigator in a project investigating leadership diversity in organisations. Funded by the Australian Research Council, the project is looking at the ways in which some people reach senior positions and others do not.

The research, says Pullen, shows that while organisations have policies and initiatives to support an inclusive and diverse workforce, those measures are not changing the relationships between people organisationally, nor changing workplace cultures that do not foster inclusiveness.

It underlines a key question: instead of putting the focus on what women need to do, how do organisations need to change?

“We have been having those arguments for decades, yet things have been very slow to change,“ Pullen says.

“Usually, such policies come out of departments that are dedicated to equality and diversity, but what counts is the way in which these policies get picked up and used in the every day workings of everybody in the organisation, particularly line managers.

“You can have the best policies in place, but if they are not embedded into the managerial roles and practices of those people managing the bright young women coming through, they make no difference.”

Until organisations truly support diversity, women’s rise to positions of power will continue to happen against the odds, Pullen says.

“We need to ask organisations to be responsible for ensuring that they have diverse workforces at all levels of the organisation.”

This article was first published on The Lighthouse by Macquarie University. Click here to read the original story.

Looking for more inspirational reads this International’s Women’s Day?