The ability of the Albert’s lyrebird to mimic sounds is world-famous. However, a recent study has shown that they could be losing their voice if more isn’t done to protect their habitat.

Lyrebirds are one of the animal kingdom’s greatest mimics: famous for their phenomenal ability to imitate sounds made by other birds. Males are also well-known for their impressive mating dance and visual display.

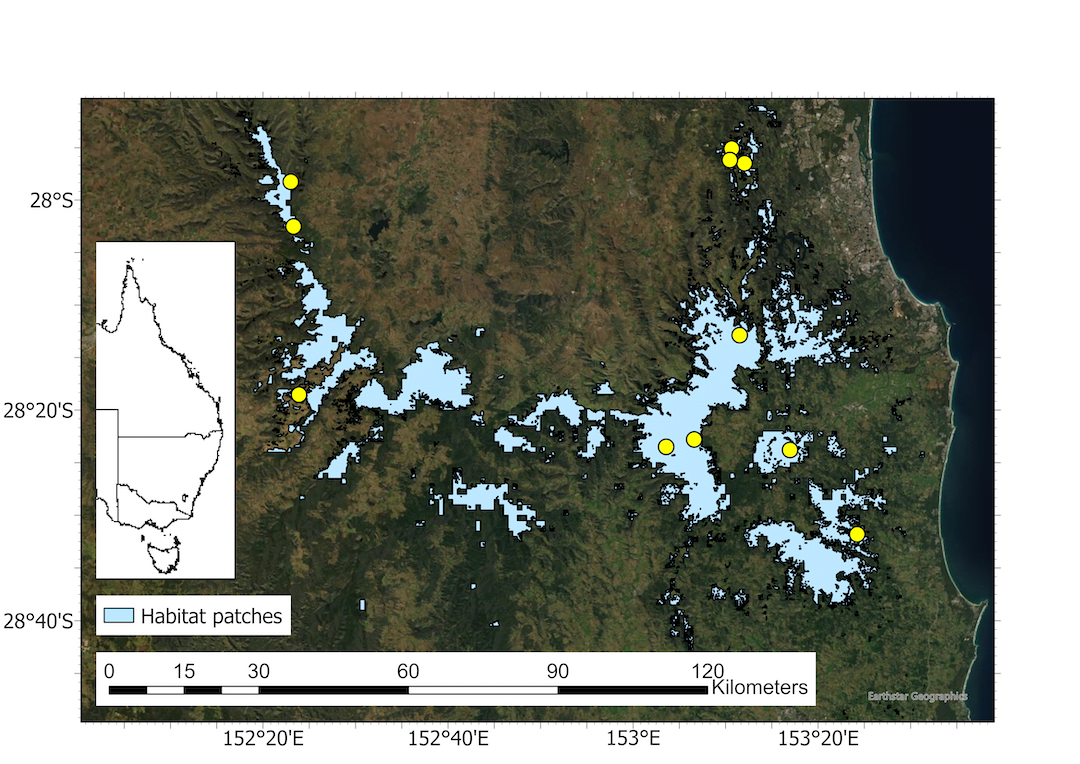

The Albert’s lyrebird is the lesser known of Australia’s two lyrebirds (the most well-known being the Superb lyrebird). It is a shy, solitary bird, only found in a small region of subtropical rainforest in the mountainous areas of Bundjalung Country, on the border between New South Wales and Queensland.

A recent study by Western Sydney University’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment has found that the Albert’s lyrebird is in danger of losing its song. We spoke to the leading researcher, PhD student Fiona Backhouse, about why this might be the case.

Landscape typical of the Albert’s lyrebird habitat. Image: Fiona Backhouse.

Call of the wild

Fiona was initially drawn to studying lyrebirds due to an early interest in music. “When I found out that you could study birdsong, almost like you can study music, that was just fascinating to me,” she says.

To gather the data for the study, Fiona and a small team recorded the Albert’s lyrebird over two winter breeding seasons in different locations, including Mount Tambourine, Lamington National Park, the Border Ranges National Park, Jerusalem National Park, and Main Range National Park.

Using handheld recording devices, she aimed to record as many lyrebird songs as possible – even if it meant waiting for long periods of time out in the cold. She also used an automated sound recording device, which she could leave behind to record for a certain amount of time each day.

Lyrebirds can mimic 11 different species, with up to 37 different sounds. One of the questions Fiona is frequently asked is how she knows the difference between a lyrebird call or the original species.

“It’s something that you have to get your ear in for,” she says. “One of the tricks is that they mimic in a string of mimicry that’s quite predictable. If you’re hearing a kookaburra, a satin bowerbird, a rosella and then a robin all from the same spot, you can be pretty sure it’s a lyrebird. But they also have their own songs that they sing fairly regularly, so you can keep an ear out for that.”

The Albert’s lyrebird is a timid and solitary bird. Image: Imogen Warren.

A social network

From these recordings, Fiona was able to interpret that there was less diversity in the lyrebirds’ songs.

“What’s happening is that individuals in areas that have less available habitats are mimicking fewer sounds from different species and fewer species overall,” explains Fiona. “While the species they mimic are still found across all of the areas that we studied, what we think is happening instead is that there are actually fewer and more isolated lyrebirds in these areas.”

This is because lyrebirds predominantly learn their songs from each other, rather than from the birds they hear around them – this is called social transmission. It forms part of the birds’ culture, and as the songs are passed between birds over generations, they change and adapt over time and geographic location.

“If there are fewer lyrebirds around for them to learn from, they’re probably not going to be able to sing in quite as big a diversity as in areas where there are lots of lyrebirds,” Fiona says.

The destruction of habitat leading to small, unconnected areas is particularly detrimental to these large, solitary birds. As lyrebirds are poor flyers and unable to travel large distances, they need substantial connected areas of habitat for movement and cultural exchange between populations.

Continued habitat loss, particularly for those populations already impacted, could therefore mean further loss of cultural diversity. And, as the vocal displays and mimicry of male lyrebirds are mostly targeted towards females, the males in these areas may no longer be as attractive as a mate. This could lead to populations getting even smaller, and the loss of even more songs.

While researchers aren’t sure whether this is happening to such an extent yet, Fiona says that it’s definitely a possibility and something that we should be concerned about.

Habitat distribution of the Albert’s lyrebird. Image: Fiona Backhouse.

Population peril

The Albert’s lyrebird is already very vulnerable to population loss. There’s estimated to be fewer than 10,000 individuals in the wild, and females only lay one egg each year. The rates of nest predation can be quite high. “If something like a feral cat or fox comes and takes the egg, that’s it until next year,” says Fiona.

Habitat availability can be impacted by development, climate change and bushfires. In the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020, an estimated 3 billion animals were killed, injured or displaced, and Fiona suspects the fires also had a negative impact on Albert’s lyrebird populations.

“At state level, they are still listed as either vulnerable in New South Wales or near threatened in Queensland. So there’s a bit of discrepancy there about whether they are threatened or not.”

While researchers are not sure whether the population is decreasing, Fiona says that the most important thing is to protect the current population. “The main issue is just there’s not very many of them, so we really need to make sure that we can protect what’s there.”

The most important thing we can do to protect the Albert’s lyrebird is to protect their habitat. Image: Imogen Warren.

Looking to the future

What are some of the steps that we can take towards protecting the Albert’s lyrebird?

“The biggest thing at the moment is to maintain their habitat,” says Fiona. “We need to make sure that we don’t take away any existing habitat, protect what’s there and stop invasive weeds. There are some programs around Murwillumbah in the Tweed basin to remove things like lantana, which is a really noxious weed in the area, and helping to revegetate some of the rainforests that were in those areas. So that’s fantastic. If we can continue those efforts, I think that’ll be really helpful for lyrebird populations.”

While this particular study is now complete, Fiona is not done with lyrebirds just yet. Her next project involves a study of both the Albert’s and Superb lyrebirds, exploring their dance and amazing visual displays, as well as further research into mimicry.

Did you know?

It’s not just male lyrebirds that sing. Females also have their own mimicry and songs. Females sing to defend their territory against other females, and also to protect their nests from predators.

For more amazing stories about our environment, check out the new discovery of a bioluminescent millipede.