There are more than 3500 tailings dams around the world. 3500 recipes for distaster.

Tailings are the fine-grained solid residues left after minerals and metals have been extracted from an ore. They are commonly transported as slurry and thickened before being stored in tailings dams.

When Vale’s tailings dam near the Brazilian city of Brumadinho burst, it killed hundreds of people. It also threatened global iron supplies and reset the conversation on tailings dam safety. On 25 January 2019, Tailings Dam I of the Brazilian mining giant’s Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine collapsed. It flooded the valley below with a 12 million cubic metre cascade of thick brown tailings sludge that swallowed the mine’s offices and its packed cafeteria. It enveloped farms, the hamlet of Vila Ferteco and buildings on the outskirts of the city of Brumadinho. Official figures state that 272 people died in the disaster, including 14 whose bodies have never been recovered.

In the aftermath of the disaster, Vale’s stock price plummeted 24 per cent. This was followed by the launch of a far-reaching, ongoing criminal investigation. The company’s viability is being questioned after numerous entities launched the largest lawsuit in UK history after a previous disaster; the 2015 Samarco Mariana dam collapse. That failure killed 19 people and virtually destroyed the nearby villages of Bento Rodrigues and Paracatu de Baixo. It does not take much imagination to expect that similar suits will follow the Brumadinho disaster.

Failure leads to frenzy

There are more than 3500 tailings dams worldwide. According to Richard Williams from process engineering company McLanahan’s International, “there are one or two tailings dam failures a year”. The 2019 failure seriously threatened the global iron ore supply. Frenzied trading pushed prices up 18 per cent in a fortnight. This pushed the commodity price towards 2014 levels as other miners struggled to lift production.

Another impact was the effect the disasters had in the boardrooms of the world’s major mining companies. In December 2016, the International Council on Mining & Metals, which encompasses the 27 leading mining companies in the world, put out a position statement bluntly titled ‘Preventing catastrophic failure of tailings storage facilities’. In September 2019, the Minerals Council of Australia followed up with the Australian Mining Tailings Communique; a document developed in concert with its members. The communique acknowledged that “tailings management in Australia is advanced and highly regulated but focuses on demonstrating global leadership and best practice in governance, information sharing and technical expertise in tailings storage management. The communique also seeks to solidify the industry focus on preventing a repeat of past tailings storage errors.”

Moves to manage the risk

The mining equipment, technology and services sector has demonstrated a new willingness to invest in tailings storage management and safety. Williams says “without a socially acceptable plan to responsibly deposit and rehabilitate these areas, you have no project and the community expectation appears moving to some form of dry tailings. Multiple technology options exist currently to produce and stack dry tailings. There are no technical limits to achieving this, only a cost implication. As society accepts the need to eliminate tailings dams and loss of life, the industry should move in parallel to improve safety and reliability in these areas.”

He adds: “A number of McLanahan customers are currently assessing how ‘filtered tailings’ could fit into their resource expansion projects. When we configure a filtered tailings solution, we typically aim for a closed loop or zero pond tailings management strategy. For a closed loop tailings system, quarry operators are encouraged to consider an ultra-fines recovery system, where potentially usable ultra-fine product can be reused as a blend medium or for other products, rather than sending it straight to waste.”

“Quite simply, product fines that would go to a pond can now be redirected to a thickener, where they are densified, and process water is captured for plant reuse. The thickener underflow is pumped to a mixing tank and run through a filter press, where the solids are further dewatered and a dry cake is produced. The filtrate (water) is also captured from this process for reuse or disposal to alternative markets.”

One door closes, another one opens

While there is a definite move towards dry processing of tailings, there are thousands of tailings storage facilities in existence. A key challenge for mining companies is monitoring the status of both open and closed tailings facilities.

According to Inmarsat’s Mining Innovation Director Joe Carr, “there is a wide range of methods used across the industry for collecting data at tailings dams. But the vast majority typically rely on manual processes … This manual approach to data collection commonly leads to human error in the reporting of metrics, which leads to a lack of consistency in reporting, making it difficult for mining companies to obtain a complete view of the conditions at their tailings facilities.”

“The net effect of this is that mining companies often have a disjointed and siloed approach to managing tailings dams, which they struggle to access, comprehend and use any data they collect. It is a particular problem for mining companies with global operational footprints; they often struggle to bring the data together from their tailings dams across the world to a central place. Furthermore, even the larger companies that have more sophisticated multi-sensor systems may have a completely different arrangement at another dam. This makes data standardisation a difficult and inconsistent process.”

New technologies to curb loss of life

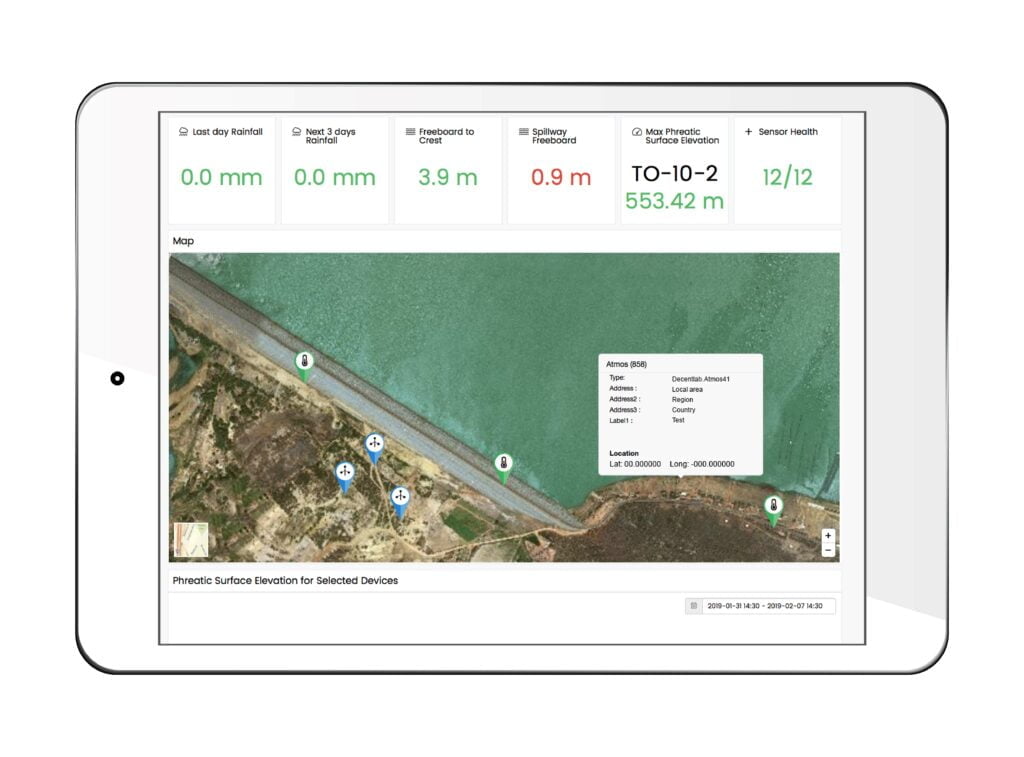

“Fortunately, there are innovative technological solutions that have been developed and implemented. These give mining companies a centralised, real-time and reliable view of the status of their tailings facilities. For example, our solution allows mining companies to gather and process data from various sensors via edge computing technologies, like LoRaWAN, and send it via our ultra-reliable L-band network to a central cloud dashboard that displays the data.”

According to Carr, the most obvious benefit of this approach is that “it allows off-site teams to manage their tailings sites more proactively by giving them a centralised and real-time oversight of key metrics, such as pond elevation, piezometric pressures, inclinometer readings and weather conditions. This means mining companies can make faster, better-informed decisions and stop any issues from developing into more serious problems. Thus, dramatically improving the safety of their dams and local communities.”

Given that two tailings dam collapses in less than 10 years have killed close to 300 people; caused massive environmental destruction; and are threatening the viability of one of the world’s largest mining companies, both the change in emphasis and the advent of new technology are very welcome developments.