Wool is trendy again among fashionistas and celebrity athletes, and the Merino wool industry is making the most of its return to global dominance.

Thinking of wool conjures images of chunky, cosy jumpers and thick scarves worn while sitting in front of a fireplace in a log cabin half buried in snow. You probably don’t think Lululemon yoga pants or Adidas running shoes – but that’s exactly where more and more Australian Merino wool is ending up. And this new boom means the Australian wool industry is making a comeback.

“It’s not so much that the industry has changed, it’s that the consumer demographic has changed,” explains Stuart McCullough, CEO of Australian Wool Innovation (AWI), a not-for-profit company owned by Australia’s 24,000 woolgrowers that invests in research, development, innovation and marketing.

“Generation Y and Millennials are pretty curious about understanding natural fibres, and the 300 million middle-class Chinese on our doorstep are eager to consume our products – the market is very different from 20 years ago,” says McCullough.

Let’s get physical

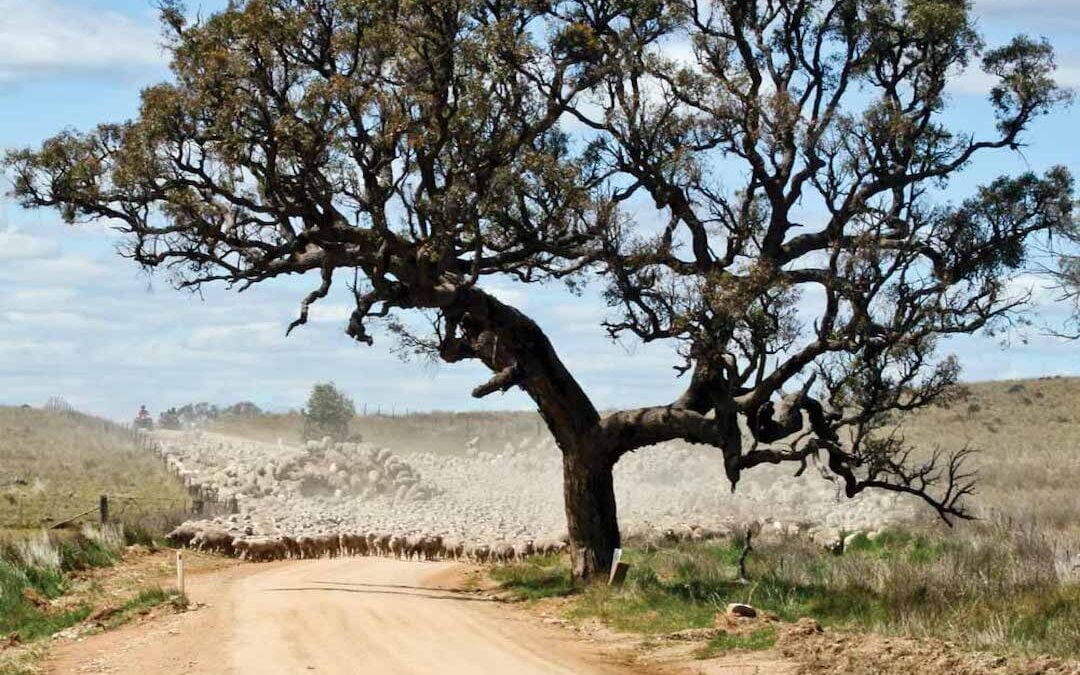

Today, the Australian wool industry is worth $3 billion a year on average, and 90 per cent of the world’s apparel wool is produced by Australian Merino sheep. In the past eight years the global price of wool more than doubled from $7.50 to $18.20 per kilogram as demand has grown, but supply remains finite – Australia’s current wool-producing flock is less than half what it was in 1990.

As brands such as Chanel and Burberry rediscover the warmth and durability of fine Merino wool, athleisure brands such as Nike and Under Armour are creating whole woollen collections that make use of the sweat-wicking, breathability and odour-absorbing qualities naturally inherent in wool.

“Traditionally wool was seen in a negative way – people remembered scratchy jumpers and skirts from the World War II era. But there is a new demand for Merino wool from the ‘next to skin’ leisurewear sector,” notes Norm Smith, owner of Glenwood Merinos in Wellington, New South Wales. “We produce a magnificent product that is completely biodegradable and recyclable, and is being used in new ways for a new generation.”

Smith is a fourth-generation wool farmer, and together with his wife Pip runs a 12,000 Merino stud and an online retail outlet selling fine Merino scarves, LoveMerino. The couple have also made sure to tap into another growing consumer trend: provenance.

“All our wool is fully traceable, with every fibre of our scarves originating from Glenwood,” says Smith. “And those who buy our wool can also prove provenance to their customers – every farm has a story.”

A strong comeback

While Smith and his family are enjoying the good times now, he still keenly remembers the pain that spread throughout the country when the wool industry collapsed 28 years ago, in February 1991. Described by Charles Massy in his book Breaking the Sheep’s Back as “the biggest corporate-business disaster in Australian history,” the crash of the Australian Wool Corporation’s (predecessor of AWI) reserve price scheme devasted the industry.

“We were being paid by the government to euthanise our sheep, and the poor quality of the wool meant we burnt a lot of bridges in key markets such as the EU,” says Smith. “It’s taken us over 20 years to rebuild our reputation and develop demand again.”

Smith, like many farmers, turned to alternative sources of income, such as creating his own products and producing lamb. In fact, where once wool was 90 per cent of his business, it is now evenly split with lamb production.

“Lamb prices have dramatically increased in recent years and there continues to be a growing demand for it,” says Will McLachlan, a fifth-generation farmer who began working with his father on their family property, Rosebank, in South Australia five and a half years ago. “Lambs are a significant piece of our business now, but we also work to get more wool from each of our sheep.”

Genetics play a strong part in today’s wool industry, with DNA testing able to predict things such as how much a lamb will grow, its resistance to infection and potential fleece weight. Though not a perfect science, breeding traits in and out of sheep can also bring in extra revenue. “Our ewe lambs are worth more for breeding than selling for meat,” says McLachlan.

A woolly debate

However, challenging Australia’s hard-fought return to the top of the global wool bale are a passionate group of people who are hard to ignore: animal activists.

“The mulesing debate is starting to drive consumers towards ethically produced wool,” explains Rick Maybury, former COO of Australian Wool Network, Australia’s largest independent wool marketer. “We need to help farmers find alternatives – animal welfare bodies represent a big challenge to the industry in the coming years.”

Already banned in New Zealand, mulesing has been a standard husbandry practice in Australia since 1927. Mulesing involves cutting a patch of skin away from the tail and breech of a very young lamb, so a scar of stretched skin grows back. The pink skin, with no wool, stays clean and dry and is unattractive to blowflies, whose eggs can cause flystrike – a condition that can be fatal.

“We stopped mulesing in 2005 due to the changing sentiment of consumers and attacks from animal rights groups, but most farmers continue the practice,” says Smith.

AWI’s longer term ambition is to work with woolgrowers to eliminate the need for mulesing, yet despite spending up to $40 million on research it has not found a solution. In 2018, it became evident that the market was demanding an end to the practice, with a $1 premium difference being paid on non-mulesed lots at auction.

Robots in the shed

Despite its past and present challenges, today the wool industry is strong and looking to the future. AWI is investing in research in multiple areas, including applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning across the supply chain, electronic sheep tags that will act as virtual fences, and the use of robotics in the beloved shearing shed.

“Shearing remains a very manual part of the supply chain, and finding shearers is getting tougher every year,” says Maybury. Australia has 73 million sheep, but only 2,800 shearers – five times fewer than 30 years ago. Many were pulled towards the resources boom to work in mines, and New Zealanders, who traditionally made up half the shearing workforce, are finding better wages at home.

The robotics lab at the University of Technology Sydney conducted a nine-month scoping study for the AWI aided by a 3D printed sheep, Shauna. Mechanical robot arms used data to reconstruct what the sheep looked like without wool to figure out where to shear. The team believed robots could be used in conjunction with manual shearing methods, not replace shearers altogether.

“When robotics was looked at in the past the cost was prohibitive, but it’s a more realistic option today,” explains Maybury. “The cost curve has come down enough that the wider industry could adopt a commercialised program.”

Wool comprises only 3 per cent of the global textile market, but Australian Merino wool remains a world leader in an increasingly important sector. Biodegradable, breathable and fashionable, wool may just be the textile of the future.

To read more about how Australian industries are making a resurgence, click here.