As city slickers spill into the regions en mass, populations and property prices are climbing.

Australia’s cities might have copped the majority of COVID cases, casualties and lockdowns throughout 2020, but a look at post-pandemic Australia suggests regional centres will see the greatest longterm transformation. The regional property boom has seen first home buyers, young families and low income households pushed even further out as median house prices in regional towns remain on track to hit $3 million by the end of 2021.

For the September 2020 quarter alone, the nation’s capitals experienced a net loss of 11,200 people – the largest quarterly net loss since the Australian Bureau of Statistics began such records in 2001.

Inevitably, as cashed up city folk with high work-from-home salaries trade multimillion dollar homes for more affordable regional dwellings, small town real estate prices are being impacted. In the year to January 2021, regional home values rose at more than four times the pace of capital city markets.

“CoreLogic’s combined regionals index was up 7.9 per cent over the 12-month period compared with a 1.7 per cent lift in combined capital city home values. As more Australians look for properties outside of the capitals, an imbalance between demand and supply is placing upward pressure on housing prices,” said CoreLogic’s executive director of research, Tim Lawless.

“Demand for regional housing can be attributed to a range of factors. Generally, prices are cheaper than their capital city counterparts, housing densities are typically lower which is likely to be appealing amidst a global pandemic, and many workers have a new found appreciation and ability to work remotely which is supporting additional demand,” he added.

Supplied by realestate.com.au

Is the regional property boom likely to last?

Even data experts are unsure of how long the regional outperformance can continue, but most agree that a permanent shift has already happened.

“As the pricing gap narrows between the regions and capital cities, the challenge of affordability will naturally drag on demand. Similarly, as the virus is more comprehensively brought under control, we will likely see more employers looking for their staff to return to the office, at least on a rostered or flexible basis,” Mr Lawless said.

“However, to some extent we expect the rise in popularity of regional markets will persist into the future. Many workers and employers have found the working from home experiment to be successful, with productivity remaining high while workers enjoy additional flexibility in their work life balance,” he added.

Simon Kuestenmacher, co-founder of The Demographics Group, said even without COVID a significant societal switch was inevitable.

“The movement of people leaving the capitals and settling in regional towns is not necessarily people escaping virus-prone cities that could go into lockdown any minute. It’s also a story of sheer demographic forces that would have occurred anyway,” he said.

“What we’ve got is by far the largest generation – 7 million Australians belong to the millennial generation – who have been living in the suburbs in one or two-bedroom apartments. This decade was always going to be when millennials needed to move to family-sized housing,” he said.

Regional centres have always been attractive to those seeking affordability, but with the regional property boom pricing young buyers out of the marker, it begs the question: can is this appetite for small town Australia be sustainable?

“The answer is a resounding ‘perhaps’ but it really depends on infrastructure,” Mr Kuestenmacher said, explaining that governments have so far failed at spreading population growth.

“Before COVID we had around 80 per cent of population growth occurring in just five cities. There’s no other country on Earth where the population is so highly concentrated in just five cities and that makes for a few peculiar housing markets,” he said.

“All the big job growth has happened in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth and Sydney so people have had to move close to those centres. Now we have a chance, because of COVID, to better spread jobs around,” he said.

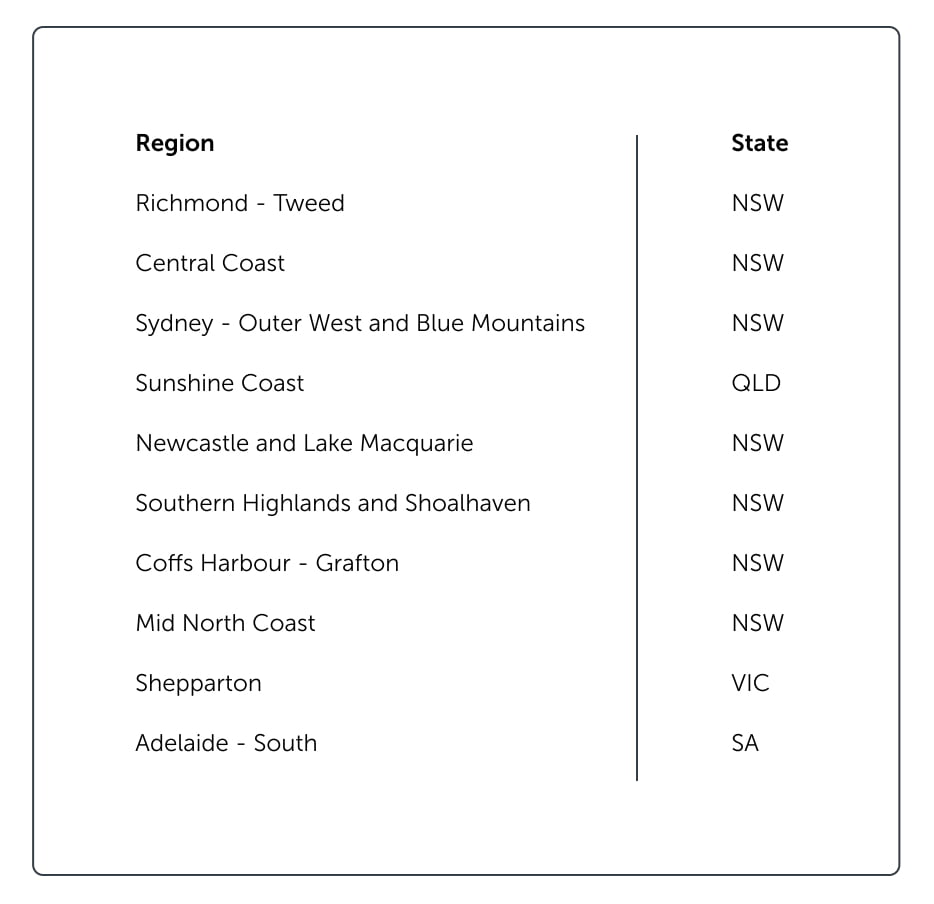

Where population and prices are climbing

A stand out example of the regional property boom can be felt in the once sleepy holiday hotspot of Byron Bay. In just one year, the median house price skyrocketed 40 per cent to $1.885 million – higher than many inner city suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne.

Nerida Conisbee, realestate.com.au‘s former chief economist noted that although such price growth is extraordinary, the demand is there.

“The value of a property is whatever someone is prepared to pay for it, so whether a home is overpriced is a matter of opinion,” she wrote.

“It is highly unusual for towns and suburbs to experience very strong price increases year on year, however, for now it doesn’t look like Byron Bay’s appeal is abating,” she said, adding that the town is on track to see median prices reach the $2 million mark in 2021.

Several non-capital city markets are even tipped to achieve $3 million median house prices this year.

“A lot of regional areas are starting to pop up in this price bracket. Somewhere like the Gold Coast, which has always been remarkably more affordable than Sydney, is getting up to that level with Main Beach potentially hitting that $3 million median,” Ms Conisbee said.

“Newcastle’s Bar Beach, could also get there after seeing incredible price growth. Then in Victoria you’ve the Mornington Peninsula, with places like Flinders and Portsea. Some of these are definitely COVID-related, primarily because people are just working differently,” she explained.

“Ultimately, there has been a really strong drive to beachside, which isn’t just because of COVID. It’s been going on for about 20 years, but it’s really starting to show up in some locations where we didn’t previously see such expensive pricing,” she said.

How to play the regional real estate long game

Simon Pressley, director of Propertyology said the global pandemic and a halt on international holidays has lead to some regional markets feeling over-cooked.

“That’s just people making decisions based on emotion and being able to afford something in the moment. Will it always be like that? The answer is no. Those stories are the exception, not the norm for regional Australia. The norm is what I’d describe as the mini capital city and there are probably 40 to 50 of them,” he said.

Mr Pressley cited the regional town of Orange in the Central Tablelands region of NSW, approximately 250kms from Sydney, as a slow burner.

“It’s arguably Australia’s most consistent property market with only one calendar year out of 20 where the median house price declined, and that decline was by 1 per cent. Sydney, on the other hand, has had six years out of 20 when the median house price declined,” he said.

“Look at Dubbo, there are 40,000 people who live in town, but there are also dozens of smaller agricultural communities and a couple of mining towns that consider Dubbo to be their capital city. Every state has a Dubbo, and most states have lots of them,” he explained.

Sustainability in a housing market, according to Mr Pressley, is less to do with the size of a town or city, and everything to do with performance.

“What defines sustainability, and reduces risk, is the economic profile and that’s what we like to educate our clients about. A location doesn’t need to be a big city to have the potential of being a really strong performer with low risk. Remember, the more you pay for an asset, the greater the risk because the further they fall – and capital cities are just more expensive,” he said.

Keen to read more on Australia’s property market?

Australian property: buying off the plan